The UK is in recession, but the real story is 13 years of stagnant wages. 0% growth in real wages is unprecedented in the post-war period. This period of flatlining growth is leading to higher taxes and fewer public services. It is an unwelcome cycle of low growth, low investment and increasing pessimism. But how bad really is the UK Economy, is there any hope on the horizon?

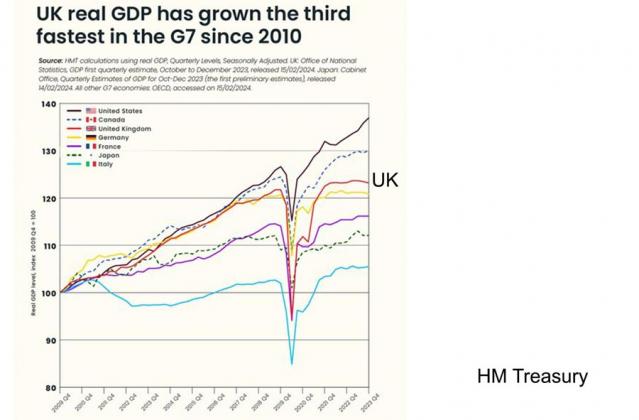

The UK treasury is keen to point out the UK real GDP growth is not too bad. But, this statistic is misleading because most the growth in GDP comes from a rise in the population.

In the past two decades, propelled by net migration, the UK population has grown from 59 to 67 million. And if we look at real GDP per capita, UK Living Standards have fallen in recent years. If we had maintained our past trend rate of growth, we would be an extra £8,000 a year per person better off. This explains why real wage growth has been so minimal and it has been quite a shock.

Because the increase in living standards we had become used to are now under threat. Will our children actually have better living standards than their parents. In recent months we have started to see very small increase in real wages, but it really is very weak, given the past falls. It will struggle to make much dent in living standards.

The good news about the current economic situation is that unemployment remains low. In the 1980s, unemployment averaged 10% and in the 1990s 8%. Today the figure is less than 4%. It is a very strange recession to have such low unemployment. But, there are two caveats.

Firstly, there has a growth in temporary, zero-hour contract type work, leading to more labour market uncertainty. Secondly, and more concerningly, there has been quite high levels of economic inactivity. Not classified as unemployed, but not working either. Long-term sickness has risen to a record 2.8 million. Nevertheless, despite a technical recession, firms still face labour shortages in certain areas and this is a big factor behind the pressure to attract immigrants to fill labour vacancies, especially in certain sectors such as care workers, NHS staff and fruit pickers and skilled vocational workers, like bricklayers and plumbers. The UK scores well on university education, but lack of skilled vocational workers is a constraint on growth.

When looking at an economy, it is also important to look beyond headline statistics. Average wage growth is stagnant, but different groups of workers have fared very differently. During the inflation spike, higher food and energy prices hit low income families with a higher inflation rate. At the same time, a benefit freeze, especially on housing benefits has hit low-income households most significantly. It is the poorest likely to see the biggest squeeze in living standards, and after housing costs there is a worrying rise in poverty levels. There has been an unequal effect of the cost of living crisis, edging UK inequality up, after several years of improvement.

Whilst, the UK has struggled to grow income, the past decade has seen more impressive growth in wealth. The ratio of wealth to income has increased. This was partly driven by the period of low interest rates and quantitative easing, which saw house price-to-income ratios soar. This created winners and losers. With homeowners who bought 15 years ago, sitting on equity gains, but a new generation of households facing an unpalatable choice of high rents or very difficult to get a mortgage. Unsurprisingly the ratio of young people becoming a homeowner has plummeted in the UK. The housing crisis has worsened effective living standards more than real wage figures suggest. The UK has one of the worst housing markets for low income groups. But it is not confined to low income groups. Even those with above-average wages can struggle to find good housing, especially in the south.

The problem is that there seems little solution to this housing crisis. Higher interest rates and inflation, combined with weak demand have seen building rates fall in 2023. The government have a target of 300,000 but 2023 is likely to see the target appear ever further away. One study suggests a shortfall of 4 million homes. But, building homes where they are needed is going to be a monumental challenge, especially with the population forecast to rise to 76 million in the next 20 years.

Whilst the UK economy has experienced many global headwinds such as Covid, and oil price shock, the economy is also struggling with the effects of a Brexit deal which has been very disruptive to European trade. Historically, the UK was one of the most open countries to trade, with trade a major source of growth. But, since the Brexit deal, firms have faced higher tariffs, more regulations and custom barriers. In 2024, new regulations are still coming into force which are particularly damaging for the food industry.

Analysis by OBR and UK in a changing Europe, estimates the net cost of Brexit is around 4-5% of GDP compared to had the UK stayed in the single market. This cost is spread out over 15 years – reducing growth rates by an average of 0.3% per year. The net loss is an estimated £2,500 per person smaller, with a corresponding fall in tax revenue. So far, free trade deals with the US have not materialised and the Canadian one is under review due to issues over agriculture.

The uncertainty of Brexit, led to a drop off in business investment from 2016. This is particularly a problem for the UK since we have consistently had low levels of investment. Whilst private sector investment is weak, it is not helped by falling levels of public investment, with a government cutting often cutting back on public investment to meet debt rules.

When examining an economy it is also not just about an individual wages. There is private wealth and public weatlh. Living standards are also determined by the state of public resources. For example, the NHS has faced a sharp rise in waiting lists. Total waiting lists in England have risen from 2.5 million in 2010 to a near all time high of 7.6 million. The NHS is one government department which has seen significant rises in real spending, but despite this has struggled to keep up with an ageing population. And it’s not just about money, productivity growth in the public sector has been near zero – a real problem. Other departments not protected, have seen real cuts. Education, the legal system, local councils and the environment have all struggled with stringent spending cuts. On this grounds, the outlook is really quite concerning. The government have reluctantly increased tax rates to one the highest share of GDP for decades. There is a likelihood that taxes will be cut in March, but if that happens, it will be at the expense of lower spending elsewhere. The head of the OBR has recently criticised the government’s spending forecasts because they are based on arbitrary figures with no detail on how the cuts will be achieved.

Since reaching a post-war low of 33% in 2000, UK public sector debt rose sharply in the financial crisis and has continued to rise due to Covid, low growth and ageing population. The rise in debt is particularly concerning given it happened despite austerity and stringent spending limits. With low economic growth, the government faces an unwelcome trade off of having less money to fund higher demand for public services. Debt is forecast to rise for the next four years, but this forecast is based on very optimistic forecasts of holding back government spending.

If that all sounds a bit depressing there is at least one piece of good news for the UK economy, in the past six months, inflation has fallen and, helped by falling gas prices, is forecast to fall back to the Bank of England’s inflation target later in the year. The Bank of England has received considerable criticism. Even an ex-member of the Bank Andrew Haldane admitted QE went on too long and monetary policy was too loose at the end of Covid. But, the UK inflation experience was not that much dissimilar to the rest of the World and Europe in particular. However the overall increase in price levels was slightly higher in the UK than rest of Europe, which is not surprising given the huge energy shock. Another concern is that the Bank are now overcompensating for past inflation failures by maintaining relatively high interest rates even whilst inflation is falling, but pushing the economy into recession we could do without. But, the impact of monetary policy in the past two years are at best only a very minor impact on the UK’s long-term economic performance.

The long-term decline in the fortunes of UK economy can be shown by steady depreciation in the exchange rates. The Pound has fallen against both the Euro and the dollar. In fact the US provides an interesting counterpoint to the the UK and European economies. Helped by substantial fiscal expansion, the US economy has left Europe behind. But, it is more than just government deficit spending, the industrial policy of Biden did cause a surge in private investment, which is not occurring in the UK. One of the UK’s real concerns is long-term fall in productivity growth, unless this can be improved, growth and better standards will remain elusive.

The UK’s problems are not unredeemable, we are still a wealthy country, even if it is increasingly concentrated in certain cities and a smaller group of people. And by the way, that is another big problem the UK has – quite substantial regional inequality, with wealth generation focused in London and south east. Still, overall, UK GDP per capita is 23rd in the world. But, if we were grading the UK economy, it would probably be given a failing grade.

The IMF predicts the UK may grow reasonably well in the next few years, which would start to lift the gloom. In theory, the UK should have lots of spare capacity and the ability to catch up on lost ground. This could enable much higher growth. But, a more pessimistic scenario is that we increasingly resemble the likes of Italy, which has seen pretty stagnant real wages since 2000.

Sources:

https://ukandeu.ac.uk/reports/the-state-of-the-uk-economy-2024/

https://www.ft.com/content/78d3611e-a75f-4cf9-aa74-a6ac829d93b2

https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/the-long-squeeze/

This post first appeared on Economics Help Blog | Economics Help, please read the originial post: here