At first glance, 78, Banbury Road looks to be a fairly unremarkable House in a part of north Oxford’s suburbia, but closer inspection will show it was for logophiles one of the spiritual centres of lexicography. A blue plaque, inaugurated on October 21, 2002, by the then Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire, Hugo Brunner, announces that Sir James Murray lived there between 1885 and 1915.

By any stretch of the imagination, Murray was a remarkable man. Born to a tailor he quickly showed an aptitude for languages, gaining competence in some twenty-five, including Arabic, Hindi, Tongan, and ancient Gothic. Initially, he followed his father’s footsteps, becoming a tailor, then a book binder, before realising his ambition to be a teacher. He became headmaster at Hawick Academy in 1857 where he developed a particular interest in the English language.

By 1879 while he was a schoolmaster at Mill Hill School near London Murray was appointed editor of an exciting new project, the compilation of the New English Dictionary, which later became The Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Combining the task with teaching, progress was painfully slow and only the first volume, covering the words A to Ant, published in 1884, and a second, covering Ant to Batten, published in 1885, had appeared when he made the momentous decision to give up teaching, move his family, a wife and eleven children, to Oxford and devote his life to lexicography.

He moved into Sunnyside, now no 78, then the northernmost house on the east side of Banbury Road, flanked by fields owned by St John’s College. He received permission to erect a corrugated-iron building, which he called his Scriptorium, where he could work, although the College stipulated that it could not be built in the front garden. It was eventually positioned behind the house and to the north, sunk about fifteen feet into the ground so that it would not obscure the view of the next door neighbour.

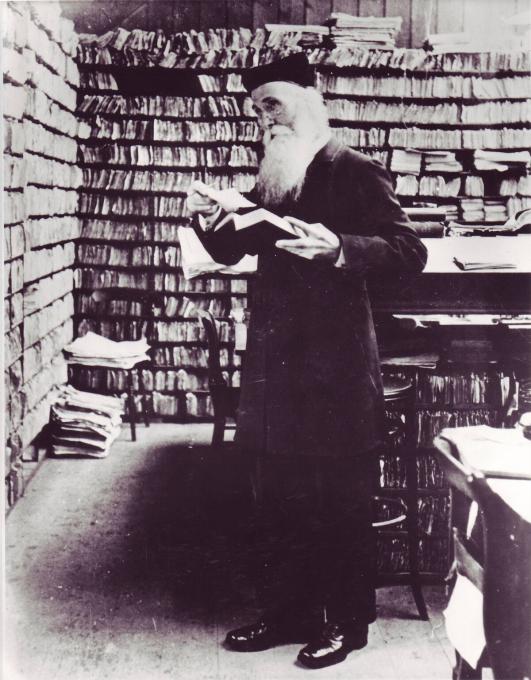

From there for the next thirty years he laboured on his Herculean task, a perfectionist often having to fend off criticism of the dictionary’s slow progress. Conditions were spartan and although there was a small stove to provide heat in winter, Murray and his assistants, including some of his children, had to wear coats to keep warm and, unsurprisingly, Murray developed pleurisy because of the conditions.

Citations and definitions of each word were laboriously transferred on to slips of paper from which they were eventually distilled into entries for the dictionary. The slips eventually weighed around three tons. Murray sent an Appeal for Readers to libraries and bookshops around the Anglophone world, inviting them to send in contributions of definitions and quotations for inclusion in the dictionary. One of the most prolific postal contributors was William Chester Minor, a murderer staying at their Majesties’ pleasure at Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane, who sent in over 12,000 citations.

Such was the volume of post generated by Murray’s operation that, rather like Father Christmas, an envelope addressed simply to Mr Murray, Oxford was enough to ensure its safe delivery. Murray and his team sent out masses of correspondence and to ease the burden of posting, the Post Office erected a post box outside his house, the first man to be accorded that distinction. As we shall see next time, though, it was no ordinary post box.

This post first appeared on Windowthroughtime | A Wry View Of Life For The World-weary, please read the originial post: here